Cuba: Te Vemos

Posted on September 16, 2016 at 3:17 PM

57 Years After the Revolution

Cuba, cut off from American travel by her island location, her dictator, the U.S. State Department, and several presidents, has always been an enigma to me. Tales of pre-Castro decadence were legendary, as was the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis that put us all on the brink of nuclear war. Whenever I would think about visiting there, I was told there was no legal way to get there.

Until now.

“We are very happy. I am very happy. Our culture creates happiness,” my guide told me in Havana in 2011 when I made my first trip to Cuba. At that time the country was about to celebrate its 53rd anniversary since the revolution that put Fidel Castro in power. Fifty-three years. It had taken all that time for a crack in U.S. policy to open long enough for me to get a visa and travel to Cuba. I was anxious to see what had happened during all of that time. I was not disappointed then and I am certainly not disappointed now, as I get ready to embark on my fifth trip to Cuba.

Fast-forward five years…

While lost in Havana one afternoon, a friend and I found a very small shop specializing in old photographs and books. The shop was so small that it was difficult for the shopkeeper and the two of us to be inside at the same time. A young man stuck his head in the open door and asked if the shop had any old medical books. I tried to squeeze to one side so he could enter. The shopkeeper gave him two—one of which was about the intestines. He chuckled as he looked at the old illustrations. The other was about yellow fever and the Cuban doctor, Carlos Finlay, who had discovered that the disease was caused and carried by mosquitoes. “He should have gotten the Nobel Prize for that,” the young man said, adding “but then again, he was Cuban, so of course not….” He asked us where we were from, and when I answered he said in perfect English that he too was from North America but was a medical student at the University of Havana. He’d been there four years already and had three to go.

The shopkeeper interrupted us handing me some photographs of a smiling, much younger, Fidel Castro, saying that he looked so happy in the photographs, a sign of the happiness of their culture. I remembered the words of my guide in 2011, “We are happy. I am very happy. Our culture creates happiness.’’ As I nodded at her, I heard the young man whisper in my ear, “Don’t believe that, about happiness, a people cannot be happy in a country that denies them free speech. Remember that.” I asked if we could meet again and he hastily scribbled his email address on the back of a card my friend handed him. He was in a rush—studying for finals and he would be going home soon for vacation, and to get out of the Havana heat, but it would be nice to meet again, to talk this over. And then he was gone. I bought the photographs of the smiling Fidel, and tucked the young man’s card in my pocket. I tried many times to reach him but the automated messages always came back saying he did not have a valid email at the address he’d given me. He did respond once, however, asking if we could meet on a Sunday afternoon—the only day he was free, and the only day my friend and I were busy, having been invited to the home of someone else we’d met in this new place of great discovery, someone who seemed, to all intents and purposes. to be very, very happy. I haven’t given up on meeting with the young man though and hope we can reconnect on my next visit. In the meantime he has given me much to think about.

I haven’t given up on meeting with the young man though and hope we can reconnect on my next visit. In the meantime he has given me much to think about.

Te Vemos

CDR

Cuba!

Slogan

Triunfo

Waiting

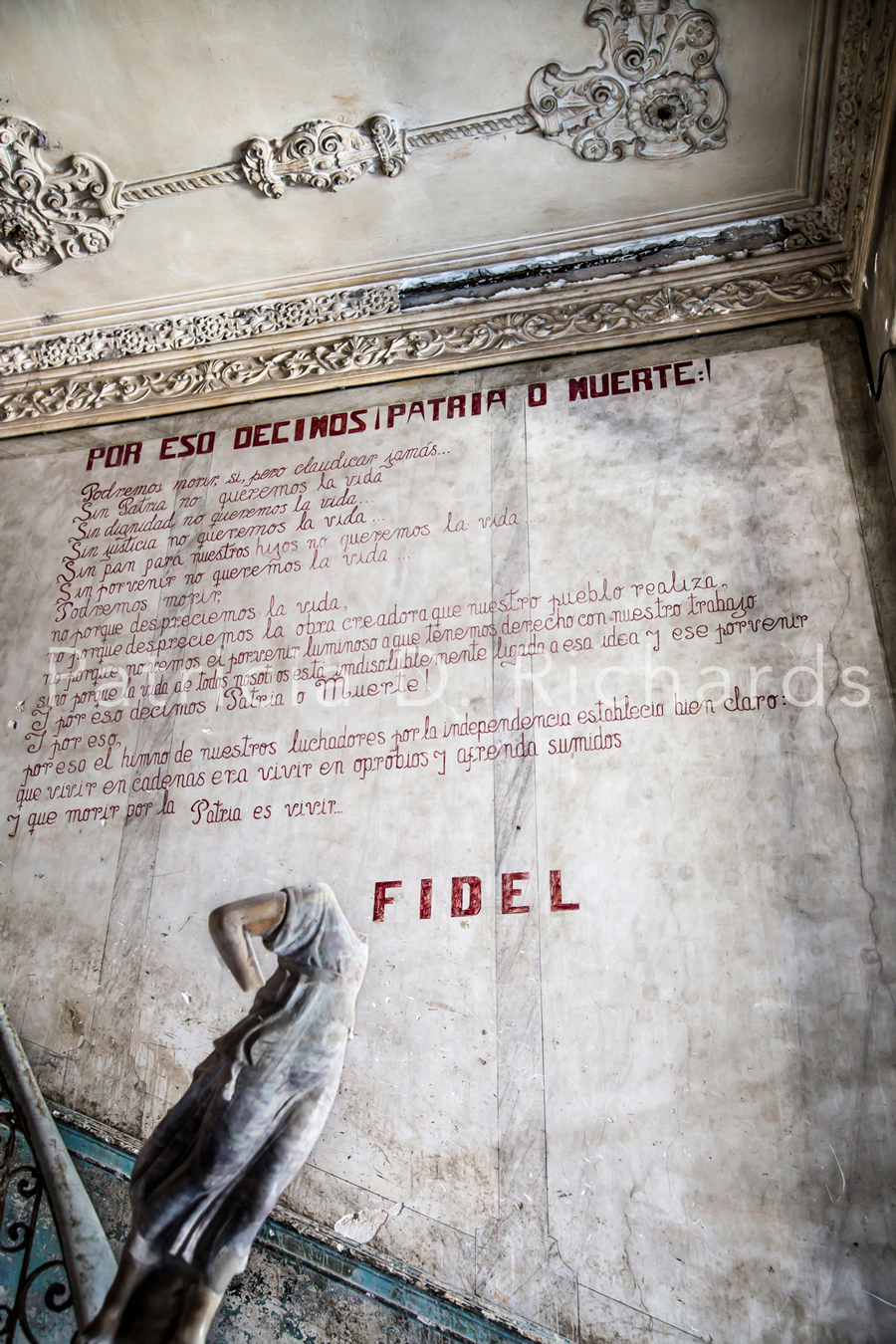

Fidel

Santiago de Cuba

Wheels

Blog Posts

Cuba: Te Vemos

“We are happy. I am very happy. Our culture creates happiness.’’ As I nodded at her, I heard the young man whisper in my ear, “Don’t believe that, about happiness, a people cannot be happy in a country that denies them free speech. Remember that.”