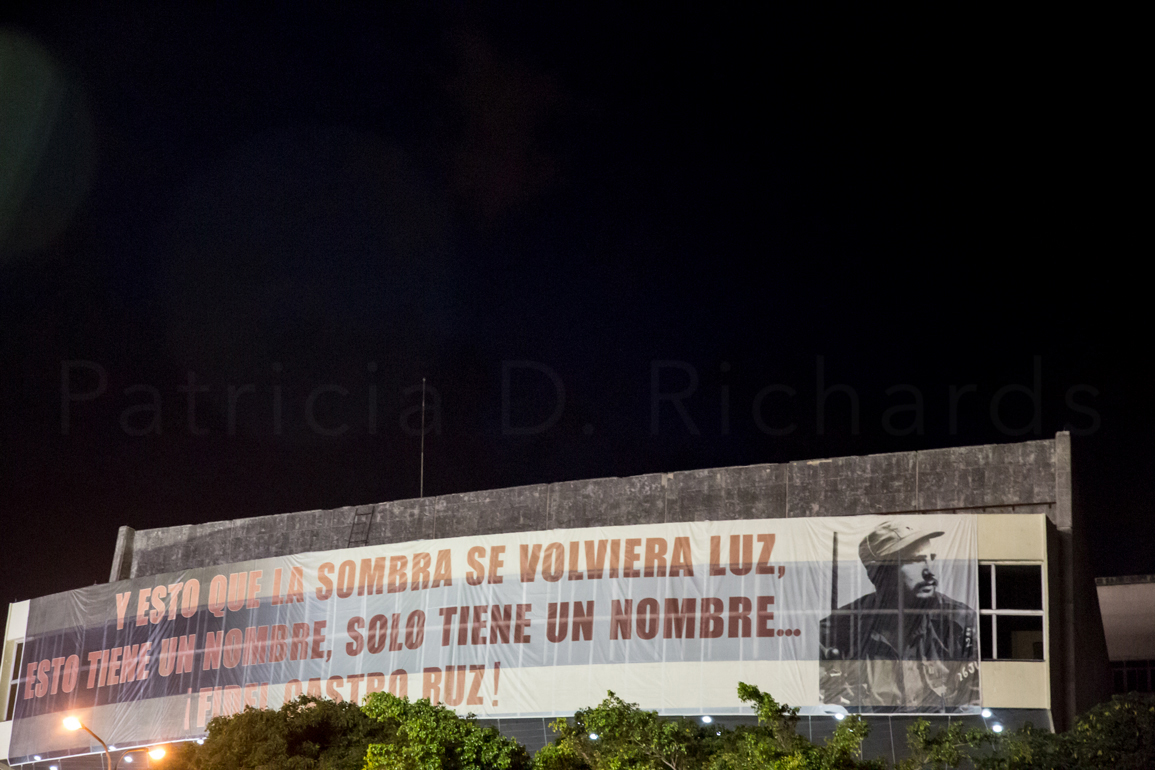

Fidel’s Final Rally

Written by Patricia D.Richards | November 29, 2016 | Havana, Cuba

At 12:07 a.m. on November 26, 2016, a three-word text message flashed across my telephone screen: “Fidel is gone!” I was shocked. I shouldn’t have been. After all I knew he was already 90 years old.

I’d traveled from one end of Cuba to the other only three months before and had seen and photographed the written greetings along the route, wishing him a happy 90th birthday. I’d joked with others that maybe he just might live forever…..and like some of them a little bit of me believed it to be so. Shocked or not, I knew I had to be in Havana on November 29 to attend his last rally. I had three days to make that happen.

Normally it would not be too difficult to make reservations and book a destination with three days to get there. But I was going to Cuba, which entailed a whole new set of obstacles. In order to get there I needed a visa. The visa office was closed for the weekend. I made airline reservations for the first flight out on Tuesday morning and secured pertinent visa information I would need in Miami. Hotel rooms were harder to find due to standing reservations by tour groups and others that were hastily made by the government for diplomats and dignitaries flying in from other countries. In the end I prevailed.

I arrived in Havana in mid-afternoon, checked into my hotel, exchanged money, grabbed my camera, and went in search of a taxi. With many streets inaccessible due to foot traffic and police regulations, the taxi driver told me he would get me as close as possible to the Plaza de la Revolución (Revolution Square) where the rally would be held, and from there he said, “Just follow the crowds.” I asked him about the likelihood of finding a taxi when it was over and he laughed. “Come back from the Square the same way you go in, and continue walking for several blocks and eventually you will probably find someone to help you.” With that, I hopped out of the car and did as I was told, I followed the crowd. It kept getting bigger. With it, I rounded a corner and went up a small incline that allowed me to see ahead, and gasped at the masses in front of me. I kept walking.

I had been to the Plaza de la Revolución many times since I made my first trip to Cuba in 2011. Indeed, it was the first place I visited upon my arrival, even before checking into my hotel. My familiarity with the 11-acre space still did not prepare me for what was to come. Never had I seen it like it was for Fidel's final rally: a crowd of massive proportions dominated every inch! Both The Guardian and The Telegraph, news agencies from the U.K., declared that “tens of thousands of Cubans” filled the square to bid farewell to Fidel that night….tens of thousands of Cubans and me.

There was no place to walk, no place to move, no place for maneuvering a way through the density of humanity that filled the square. I had only seen such things in newsreels or the movies, but had never experienced it myself. My plan was to go as far to the right as possible and then weave my way towards the left close to the front and eventually make a full circle of the square. However, once caught up in the crowd I had to let it be my guide.

At one point while trying to make my way through it, a woman seated on the ground who I almost stepped on, pulled on my pant leg and indicated my shoes were untied. There was no possible way to bend over to tie them, so she tied them for me. With the density of the crowd, it was surprising whenever I ran into (and often ran over) some who were seated because you couldn’t see them until you were upon them. They knew that hours of speeches lay ahead and wanted to stake out their territory in advance. Most, however, were standing and all were friendly. Although there was some sadness, most appeared to have gotten used to the idea over the preceding three days that Fidel Castro Ruz was dead, and that this was his final farewell.

Unlike crowds in other places in the world, there were no pick-pockets, and there was nothing for sale--no tents selling food, drinks, souvenirs, no chairs to rent, there were only those who had come to bear witness to the end of an era. Later to the repeated strains of "YO SOY FIDEL" (I AM FIDEL) uttered in unison from the crowd, I made my way out of the square and went in search of a taxi back to my hotel. After walking several blocks in the darkness, I saw a vehicle that looked like a giant orange with seats carved out of the middle. A voice said, "Lady, do you want a ride?" and a new best friend was made! As we rode back to the hotel I heard an occasional "Viva la Revolutión", "Viva Fidel", but it seemed as though it was time for the next part of Cuban history to begin. I was fortunate to have been part of it.

1492 November

Written by Patricia D.Richards | October 21, 2016 | Havana, Cuba

“In fourteen hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue,”

is the first line of a well-known poem for children that tells the story of Christopher Columbus and his discovery of the New World. It is the only line of the poem I ever learned.

During my life, I’ve lived near many places associated with Columbus’s journeys―namely, Segovia, Córdoba, Seville, Cádiz, Huelva, and Puerto de Santa Maria in Spain, and in Lisbon, Portugal. I found it exciting to learn that Columbus had been in these places, and that is how I felt when I learned Columbus had “discovered” Cuba. Realizing it is impossible to discover something that already exists, I will say instead that while sailing in the region, Columbus found Cuba. And once he found it, he declared it to be the most beautiful place he’d ever seen.

And so I decided to follow Columbus and set out for the place he had found: Baracoa, located on the southeast corner of Cuba.

It is not easy to get to Baracoa. Until the 1960s, there wasn’t even a road into the area. Here’s what I discovered:

- 1492 - Columbus found Cuba. (He left a cross behind that is located in the church.)

- 1511 - Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar followed Columbus, settled in Baracoa, and proclaimed it the capital of Cuba naming it La Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción.

- 1516 - Velázquez decided the harbor at Santiago de Cuba, located further west, was better and moved the capital to that location, abandoning Baracoa.

And so Baracoa stayed the way it was, isolated and abandoned by the outside world. Of course, the Baracoans knew of it because they lived there. However, there was no way into the area other than by sea for 400 years…400 YEARS! As a result, Baracoa developed on its own. The architecture is different from other places in Cuba; horse-drawn carts and bicycle taxis are the common means of transportation, and everyone knows everyone. It is the people who elevate this place. They are of Baracoa. They have lived off this land for 505 years. They have a feel for their tropical geography and the climate in which they live―(Did I say it was hot? humid? Yikes!)―they are attached to it and to one another, and they are welcoming to outsiders

It was in Baracoa that I met Renato. He spent his day off from work showing me his connections to this incredible place, explaining its significance, and why he needs to be there. By day’s end, I was convinced that following Columbus had been one of the smartest decisions of my traveling life.

And then Hurricane Matthew struck. Packing winds of 145 mph, it hit Baracoa with a disastrous punch. I didn’t hear from Renato for several days; it was difficult to get any information out of Cuba.

Finally, a message arrived: “We are destroyed,” he wrote.

Here are his pictures.

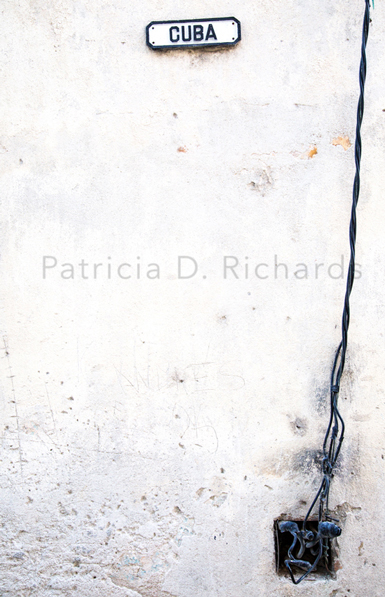

Cuba, Cuba

Written by Patricia D.Richards | September 16, 2016 | Havana, Cuba

Cuba, a street in Havana, is like all streets in Havana, fascinating. I found it quite by accident while exploring the city and decided to follow it. The irony of being on a street named ‘Cuba’ while in Cuba was not lost on me. As I neared the end of Cuba, I discovered a bonus—a boxing school. I had not set out to photograph boxing hopefuls on this day, or to find the school that in fact I didn’t know existed. However, from my vantage point outside I could see kids practicing in the open air. I went in.

Catching the eye of the instructor, I pointed to my camera and he nodded his consent. I knew enough to stay out of the way, and set to work. While there I was reminded of the inherent rhythms by which we live, the ways our bodies move through space, and the ways in which photography becomes a part of those same rhythms.

Three groups proceeded towards greatness that afternoon: the young boys learning how to protect themselves, the more professional tattooed man who trained with purpose, and the little boys, sitting in the stands, waiting their turns to move into the ranks of class members. In the end the instructor asked for a group picture. I was only too happy to oblige.

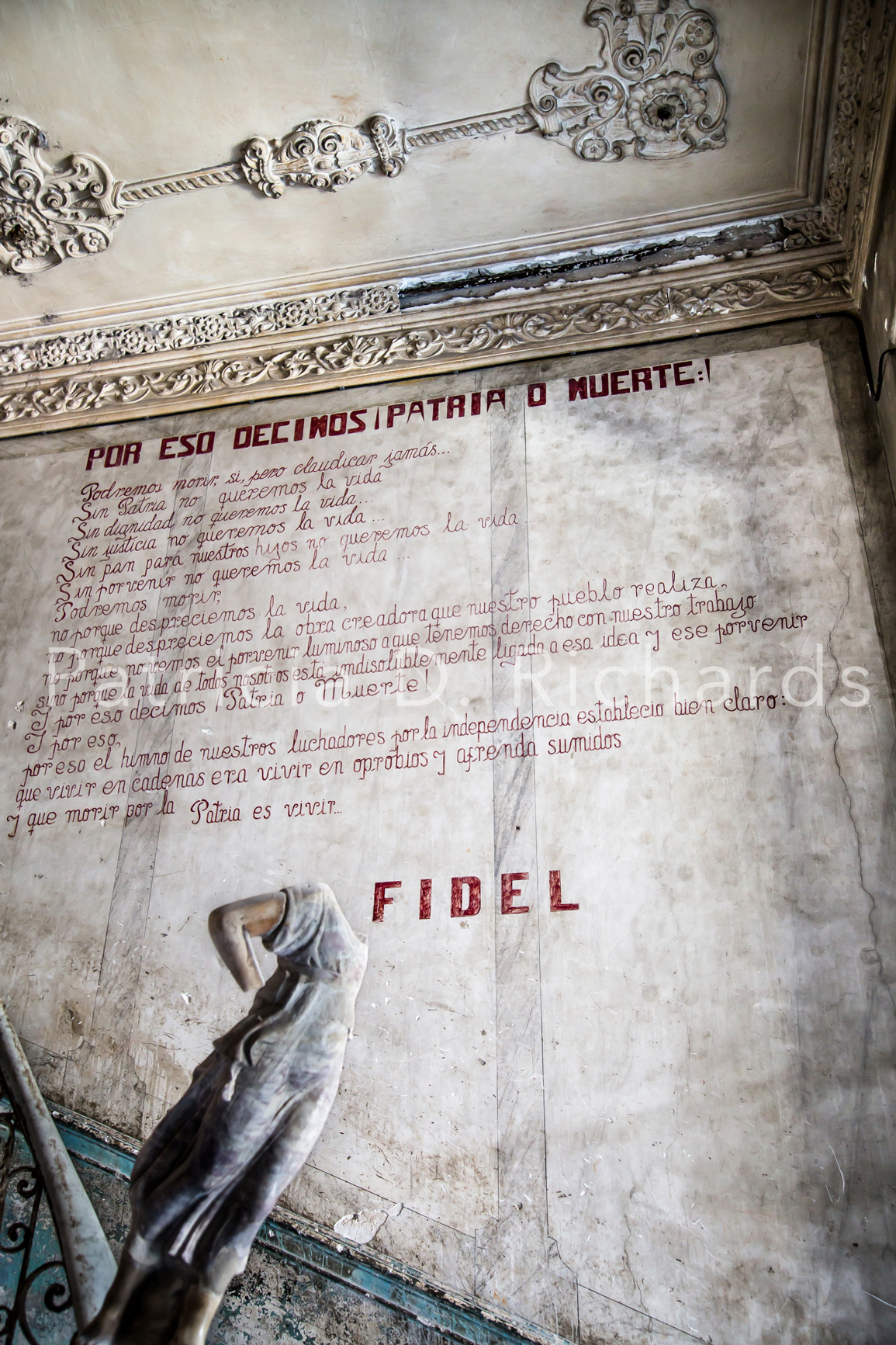

Cuba: Te Vemos

Written by Patricia D.Richards | August 12, 2016 | Havana, Cuba

57 Years After the Revolution

Cuba, cut off from American travel by her island location, her dictator, the U.S. State Department, and several presidents, has always been an enigma to me. Tales of pre-Castro decadence were legendary, as was the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis that put us all on the brink of nuclear war. Whenever I would think about visiting there, I was told there was no legal way to get there.

Until now.

“We are very happy. I am very happy. Our culture creates happiness,” my guide told me in Havana in 2011 when I made my first trip to Cuba. At that time the country was about to celebrate its 53rd anniversary since the revolution that put Fidel Castro in power. Fifty-three years. It had taken all that time for a crack in U.S. policy to open long enough for me to get a visa and travel to Cuba. I was anxious to see what had happened during all of that time. I was not disappointed then and I am certainly not disappointed now, as I get ready to embark on my fifth trip to Cuba.

Fast-forward five years…

While lost in Havana one afternoon, a friend and I found a very small shop specializing in old photographs and books. The shop was so small that it was difficult for the shopkeeper and the two of us to be inside at the same time. A young man stuck his head in the open door and asked if the shop had any old medical books. I tried to squeeze to one side so he could enter. The shopkeeper gave him two—one of which was about the intestines. He chuckled as he looked at the old illustrations. The other was about yellow fever and the Cuban doctor, Carlos Finlay, who had discovered that the disease was caused and carried by mosquitoes. “He should have gotten the Nobel Prize for that,” the young man said, adding “but then again, he was Cuban, so of course not….” He asked us where we were from, and when I answered he said in perfect English that he too was from North America but was a medical student at the University of Havana. He’d been there four years already and had three to go.

The shopkeeper interrupted us handing me some photographs of a smiling, much younger, Fidel Castro, saying that he looked so happy in the photographs, a sign of the happiness of their culture. I remembered the words of my guide in 2011, “We are happy. I am very happy. Our culture creates happiness.’’ As I nodded at her, I heard the young man whisper in my ear, “Don’t believe that, about happiness, a people cannot be happy in a country that denies them free speech. Remember that.” I asked if we could meet again and he hastily scribbled his email address on the back of a card my friend handed him. He was in a rush—studying for finals and he would be going home soon for vacation, and to get out of the Havana heat, but it would be nice to meet again, to talk this over. And then he was gone. I bought the photographs of the smiling Fidel, and tucked the young man’s card in my pocket. I tried many times to reach him but the automated messages always came back saying he did not have a valid email at the address he’d given me. He did respond once, however, asking if we could meet on a Sunday afternoon—the only day he was free, and the only day my friend and I were busy, having been invited to the home of someone else we’d met in this new place of great discovery, someone who seemed, to all intents and purposes. to be very, very happy. I haven’t given up on meeting with the young man though and hope we can reconnect on my next visit. In the meantime he has given me much to think about.

I haven’t given up on meeting with the young man though and hope we can reconnect on my next visit. In the meantime he has given me much to think about.